Vertical sex segregation: Difference between revisions

(Creating page) |

(Creating page) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

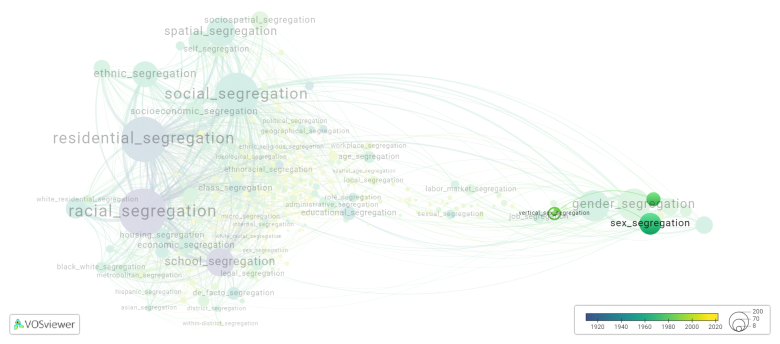

[[File:vertical_sex_segregation.png|780x780px]] | [[File:vertical_sex_segregation.png|780x780px]] | ||

This visualization is based on the study [[ | This visualization is based on the study [[Segregation_Wiki:About| The Multidisciplinary Landscape of Segregation Research]]. | ||

For the complete network of interrelated segregation forms, please refer to: | For the complete network of interrelated segregation forms, please refer to: | ||

Latest revision as of 07:17, 16 October 2024

Date and country of first publication[1][edit | edit source]

1993

Australia

Definition[edit | edit source]

Vertical sex segregation refers to the concentration of men and women in different occupational fields or industries, with men typically being overrepresented in higher-paying and more prestigious positions while women are more often found in lower-paying and lower-status roles. This segregation can be observed across many sectors of the economy, including business, politics, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and even within specific professions such as law and medicine.

There are several factors that contribute to vertical sex segregation. These include societal norms and expectations about gender roles, stereotyping, discrimination, lack of access to education and training, biased hiring and promotion practices, as well as work-family conflicts and gendered expectations for caregiving responsibilities.

Vertical sex segregation is considered a form of gender inequality and can have significant implications for women in terms of their earnings, career advancement opportunities, and overall economic well-being. It contributes to the gender wage gap, limits women's representation in leadership positions, and perpetuates gender stereotypes and biases.

Efforts to reduce vertical sex segregation include implementing policies and practices that promote gender equality and diversity in the workplace, providing equal access to education and training opportunities, addressing biases and stereotypes, promoting work-life balance, and supporting women's career advancement.

See also[edit | edit source]

Related segregation forms[edit | edit source]

Vertical sex segregation is frequently discussed in the literature with the following segregation forms:

vertical segregation, sex segregation, occupational segregation, occupational sex segregation, horizontal sex segregation

This visualization is based on the study The Multidisciplinary Landscape of Segregation Research.

For the complete network of interrelated segregation forms, please refer to:

References[edit | edit source]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Date and country of first publication as informed by the Scopus database (December 2023).

At its current state, this definition has been generated by a Large Language Model (LLM) so far without review by an independent researcher or a member of the curating team of segregation experts that keep the Segregation Wiki online. While we strive for accuracy, we cannot guarantee its reliability, completeness and timeliness. Please use this content with caution and verify information as needed. Also, feel free to improve on the definition as you see fit, including the use of references and other informational resources. We value your input in enhancing the quality and accuracy of the definitions of segregation forms collectively offered in the Segregation Wiki ©.

Vertical sex segregation appears in the following literature[edit | edit source]

Watts M. (1993). Explaining trends in occupational segregation: Some comments. European Sociological Review, 9(3), 315-319. Oxford University Press.https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036683

Stover D.L. (1994). The Horizontal Distribution of Female Managers within Organizations. Work and Occupations, 21(4), 385-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888494021004003

Küskü F., Özbilgin M., Özkale L. (2007). Against the tide: Gendered prejudice and disadvantage in engineering. Gender, Work and Organization, 14(2), 109-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00335.x

Seierstad C., Opsahl T. (2011). For the few not the many? The effects of affirmative action on presence, prominence, and social capital of women directors in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 27(1), 44-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2010.10.002

Seierstad C., Healy G. (2012). Women's equality in the Scandinavian academy: A distant dream?. Work, Employment and Society, 26(2), 296-313. SAGE Publications Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011432918

Nemoto K. (2013). When culture resists progress: Masculine organizational culture and its impacts on the vertical segregation of women in Japanese companies. Work, Employment and Society, 27(1), 153-169. SAGE Publications Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012460324

Berkers P., Verboord M., Weij F. (2016). “These Critics (Still) Don’t Write Enough about Women Artists”: Gender Inequality in the Newspaper Coverage of Arts and Culture in France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States, 1955 2005. Gender and Society, 30(3), 515-539. SAGE Publications Inc..https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243216643320

Nemoto K. (2016). Too few women at the top: The persistence of inequality in Japan. Too Few Women at the Top: The Persistence of Inequality in Japan, 1-282. Cornell University Press.https://doi.org/