Sectoral segregation: Difference between revisions

(Creating page) |

(Creating page) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Overall, sectoral segregation refers to the concentration of industries or sectors in specific areas and can have both positive and negative implications on economic development and regional disparities. | Overall, sectoral segregation refers to the concentration of industries or sectors in specific areas and can have both positive and negative implications on economic development and regional disparities. | ||

===== Synonyms ===== | ===== Synonyms ===== | ||

The following terms are synonymous with: | The following terms are synonymous with sectoral segregation: | ||

sectorial segregation. | sectorial segregation. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Sectoral segregation is frequently discussed in the literature with the following segregation forms: | Sectoral segregation is frequently discussed in the literature with the following segregation forms: | ||

gender | [[gender segregation]], [[sectoral gender segregation]], [[horizontal segregation]], [[job segregation]], [[occupational segregation]] | ||

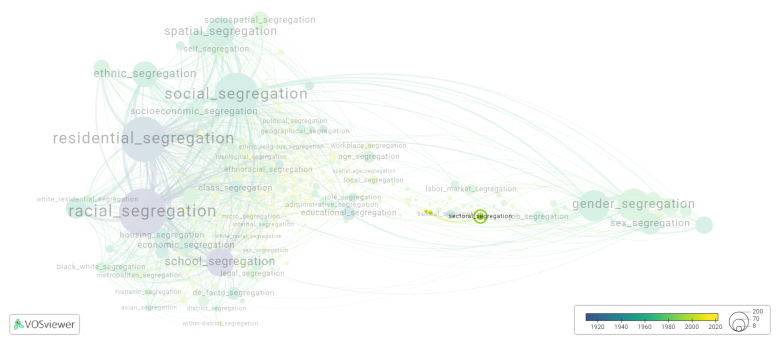

[[File:sectoral_segregation.png|780x780px]] | [[File:sectoral_segregation.png|780x780px]] | ||

This visualization is based on the study [[Segregation_Wiki:About| The Multidisciplinary Landscape of Segregation Research]]. | |||

For the complete network of interrelated segregation forms, please refer to: | |||

* [https://tinyurl.com/2235lkhw First year of publication] | |||

* [https://tinyurl.com/2d8wg5n3 Louvain clusters] | |||

* [https://tinyurl.com/223udk5r Betweenness centrality] | |||

* [https://tinyurl.com/244d8unz Disciplines in which segregation forms first emerged (Scopus database).] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Latest revision as of 07:17, 16 October 2024

Date and country of first publication[1][edit | edit source]

2003

Switzerland

Definition[edit | edit source]

Sectoral segregation refers to the concentration of certain industries or sectors of the economy in specific geographic areas or regions. It can occur at various levels, including national, regional, or local.

This phenomenon often occurs due to a combination of factors such as historical patterns of industrial growth, availability of natural resources, transportation infrastructure, labor availability, and specialization. As a result, certain regions may become known for their dominance in specific sectors, while other regions may lack representation or have a limited range of industries.

Sectoral segregation can have both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, it can lead to economies of scale and specialization, which can enhance productivity and competitiveness. For example, Silicon Valley in California is known for its concentration of technology and innovation companies, leading to a vibrant ecosystem and collaboration among firms.

However, sectoral segregation can also create economic disparities and vulnerabilities. If a region heavily relies on a particular industry and that industry faces a downturn, the local economy might suffer. Additionally, it can lead to uneven development and income disparities between regions.

Government policies can play a role in either promoting or addressing sectoral segregation. For example, policymakers may implement strategies to encourage diversification and attract industries to underrepresented areas. They may also invest in infrastructure and education to enhance the competitiveness of certain sectors in specific regions.

Overall, sectoral segregation refers to the concentration of industries or sectors in specific areas and can have both positive and negative implications on economic development and regional disparities.

Synonyms[edit | edit source]

The following terms are synonymous with sectoral segregation:

sectorial segregation.

References and literature addressing this segregation form under these synonymous terms can be found below.

See also[edit | edit source]

Related segregation forms[edit | edit source]

Sectoral segregation is frequently discussed in the literature with the following segregation forms:

gender segregation, sectoral gender segregation, horizontal segregation, job segregation, occupational segregation

This visualization is based on the study The Multidisciplinary Landscape of Segregation Research.

For the complete network of interrelated segregation forms, please refer to:

References[edit | edit source]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Date and country of first publication as informed by the Scopus database (December 2023).

At its current state, this definition has been generated by a Large Language Model (LLM) so far without review by an independent researcher or a member of the curating team of segregation experts that keep the Segregation Wiki online. While we strive for accuracy, we cannot guarantee its reliability, completeness and timeliness. Please use this content with caution and verify information as needed. Also, feel free to improve on the definition as you see fit, including the use of references and other informational resources. We value your input in enhancing the quality and accuracy of the definitions of segregation forms collectively offered in the Segregation Wiki ©.

Sectoral segregation appears in the following literature[edit | edit source]

Müller T. (2003). Migration policy in a small open economy with a dual labor market. Review of International Economics, 11(1), 130-143. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9396.00373

Moore S. (2009). 'No matter what I did I would still end up in the same position': Age as a factor defining older women's experience of labour market participation. Work, Employment and Society, 23(4), 655-671. SAGE Publications Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017009344871

Van Puyenbroeck T., De Bruyne K., Sels L. (2012). More than 'Mutual Information': Educational and sectoral gender segregation and their interaction on the Flemish labor market. Labour Economics, 19(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2011.05.002

Périvier H. (2014). Men and women during the economic crisis employment trends in eight European countries. Revue de l'OFCE, 133(2), 41-84. Presses de Sciences Po.https://doi.org/10.3917/reof.133.0041

Périvier H. (2014). Men and women during the economic crisis employment trends in eight European countries. Revue de l'OFCE, 133(2), 41-84. Presses de Sciences Po.https://doi.org/10.3917/reof.133.0041

Moldovan O. (2016). Representative bureaucracy in Romania? Gender and leadership in central public administration. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 2016(48), 66-83. Universitatea Babes-Bolyai.https://doi.org/

Wemlinger E., Berlan M.R. (2016). Does Gender Equality Influence Volunteerism? A Cross National Analysis of Women’s Volunteering Habits and Gender Equality. Voluntas, 27(2), 853-873. Springer New York LLC.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9595-x

Boll C., Rossen A., Wolf A. (2017). The EU Gender Earnings Gap: Job Segregation and Working Time as Driving Factors. Jahrbucher fur Nationalokonomie und Statistik, 237(5), 407-452. De Gruyter Oldenbourg.https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2017-0100

Rugina S. (2019). Female entrepreneurship in the Baltics: formal and informal context. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 58-74. Emerald Group Holdings Ltd..https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-05-2018-0055

Seneviratne P. (2019). Married women's labor supply and economic development: Evidence from Sri Lankan household data. Review of Development Economics, 23(2), 975-999. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12581

Borrowman M., Klasen S. (202). Drivers of Gendered Sectoral and Occupational Segregation in Developing Countries. Feminist Economics, 26(2), 62-94. Routledge.https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1649708

Barba I., Iraizoz B. (202). Effect of the great crisis on sectoral female employment in Europe: A structural decomposition analysis. Economies, 8(3), -. MDPI AG.https://doi.org/10.3390/ECONOMIES8030064

Barba I., Iraizoz B. (202). Effect of the great crisis on sectoral female employment in Europe: A structural decomposition analysis. Economies, 8(3), -. MDPI AG.https://doi.org/10.3390/ECONOMIES8030064

Salonen L., Kähäri A., Pietilä I. (202). Finland. Extended Working Life Policies: International Gender and Health Perspectives, 251-260. Springer International Publishing.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40985-2_18

Lewandowski P., Lipowska K., Magda I. (2021). The Gender Dimension of Occupational Exposure to Contagion in Europe. Feminist Economics, 27(1-2), 48-65. Routledge.https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1880016

Batchuluun A. (2021). The gender wage gap in Mongolia: Sectoral segregation as a driving factor. Review of Development Economics, 25(3), 1437-1465. John Wiley and Sons Inc.https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12763

Piłatowska M., Witkowska D. (2022). Gender Segregation at Work over Business Cycle Evidence from Selected EU Countries. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(16), -. MDPI.https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610202